How the String hash function works (and implications for other hash functions)

In our introduction to hash codes, we mentioned the

principal design aim of a generic hash code. By generic, we

mean a hash code that will cope with fairly "random typical" input and distribute

the corresponding hash codes fairly randomly over the range of integers (4 bytes

in the case of Java). That way, whatever the size of our hash table, we assume that

the keys will be distributed reasonably evenly among the buckets. For those that

don't want to delve too deeply into the technical details, we gave some basic

guidelines for writing a hash function.

On this page, we will delve a little more deeply into the technical details

of hash codes. As an example, we'll look specifically at the hashCode() method

used by the Java String class.

Randomness, mathematically speaking

There's actually quite a lot of overlap between the field of

random number generators

and the field of hash functions. For now, we will start by borrowing

the concept of a randomness. We will say that a number (such as a hash code) is random

if all its bits have an equal and independent chance of being either 0 or 1. Another

general concept we'll borrow is that some initial randomness has to come from somewhere.

A random number generator, is generally designed to take some unpredictable seed–

such as the number of nanoseconds since the computer was switched on–

as its initial source of randomness, and then from that generate a further

(approximately) random sequence.

Where does randomness come from?

Now let's get back to hashing the characters of a string and let's look at some typical

character data. We'll consider generating a series of random strings, where each successive

character has a particular change of being within a particular range:

- 50% of the characters are digits from 0-9; if the character has a digit,

each has an equal chance of appearing (so overall, 5% of characters will be

the digit "0", 5% will be the digit "1" etc);

- otherwise, the character is a letter;

- when the character is a letter, each letter 'A' to 'Z' has an equal

change of appearing, but on each letter there is a 50% chance that that

letter will be lower rather than upper case.

|

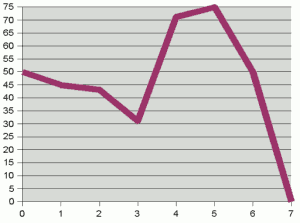

Plot of (bit number, probability of that bit being set) for

an example character distribution

|

This distribution of characters is essentially made up for illustration

purposes. But the point is that any set of strings for a particular purpose will

generally have some characteristic distribution. (There may well be interactions between

successive characters too: for example in English, u is a relatively rare

letter, but after a q becomes extremely likely as the next letter. We won't

worry too much about this here.) Now, given this character distribution, we can calcualte

the probability of each bit being set for a random character in a string. The

graph above right shows this probability distribution.

It is clear from the graph that the bits of the characters are not

randomly distributed. If they were, we'd expect to see a flat line at 50%. Instead,

the first three or four bits "hover" around and below the 50% mark– i.e. are

"more or less random"– but higher bits are heavily biased towards particular

values. For a given character, there is a better than 70% chance that bit

4 will be set, and a 75% chance that bit 5 will be set. This lack of randomness

happens almost by design– the ASCII standard was built with certain

correspondences in mind, such as bit 5 being set to mark a lower case character.

So what can we do create more-or-less random hash codes? Well, we can take

those bits that are more or less random (the low bits) and, as we build

up the hash code, try and make

them interact so that they "spread the randomness out" over the integer.

On the next page we look in more detail at spreading

the random bits in a hash function.

If you enjoy this Java programming article, please share with friends and colleagues. Follow the author on Twitter for the latest news and rants.

Editorial page content written by Neil Coffey. Copyright © Javamex UK 2021. All rights reserved.